- Home

- From Doctor Burnout to Resilient Recovery

- 5 Most Common Thinking Errors

The 5 Most Common Thinking Errors Doctors Make During Exam Prep

Preparing for high-stakes medical exams is one of the most mentally demanding experiences a doctor will face. You're juggling clinical responsibilities, long shifts, sleep deprivation, and the pressure to perform—all while trying to retain an enormous amount of information. In this environment, your mindset can either be your greatest ally or your biggest obstacle. And one of the most common obstacles? The 5 most common thinking errors—also known as cognitive distortions.

These mental traps distort reality, fuel anxiety, and undermine your confidence. But the good news? You can learn to spot and challenge them.

What Are Thinking Errors

Thinking errors are automatic, habitual thought patterns that feel true—but aren’t. They’re often irrational, emotionally charged, and deeply ingrained, especially in high-achieving professionals like doctors. These errors can distort your perception of reality, amplify stress, and sabotage your performance—particularly when you're under pressure preparing for exams.

In medicine, where perfectionism and high expectations are the norm, these thinking errors can be especially damaging. They often manifest as catastrophizing, black-and-white thinking, or emotional reasoning—leading to procrastination, burnout, and poor exam performance.

“Falling into common thinking traps increases your chances of stress, depression, or burnout.”

The 5 Most Common Thinking Errors in Doctors

Here are the five cognitive distortions most frequently seen in junior doctors preparing for exams:

| Thinking Error | Definition | Doctor-Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Black-and-White Thinking | Viewing situations in extremes—pass/fail, success/failure. | “If I don’t pass this exam, I’m not cut out to be a doctor.” |

| Catastrophising | Imagining the worst-case scenario, often irrationally. | “If I fail, I’ll lose my job, disappoint everyone, and never recover.” |

| Emotional Reasoning | Believing something is true because it feels true. | “I feel like a fraud, so I must be one.” |

| Mind Reading | Assuming you know what others think. | “My consultant thinks I’m incompetent because I hesitated during handover.” |

| Overgeneralisation | Drawing sweeping conclusions from one event. | “I blanked on one question—this proves I’m not ready.” |

Doctors are trained to be precise, responsible, and high-performing. But this culture also breeds perfectionism and fear of failure. When exams loom, these traits can morph into distorted thinking that sabotages performance.

Many doctors can internalize failure as a personal flaw rather than a learning opportunity. This mindset fuels shame, avoidance, and burnout—especially when combined with sleep deprivation and chronic stress.

Lets look at these 5 common thinking errors in more detail:

1. Black-and-White Thinking

Definition: Viewing situations in extremes—success or failure, pass or fail, competent or incompetent.

Doctor-Specific Example:

“If I don’t pass this exam, I’m not cut out to be a doctor.”

Why It’s Harmful:

This rigid mindset leaves no room for nuance. It ignores progress, effort, and learning. It turns a single setback into a total identity crisis.

How to Challenge It:

Ask: Is there a middle ground? What have I learned, even if I didn’t pass?

Reframe: “Not passing doesn’t mean I’m not capable—it means I need to adjust my approach.”

2. Catastrophizing

Definition: Imagining the worst-case scenario and believing it’s inevitable.

Doctor-Specific Example:

“If I fail, I’ll lose my job, disappoint everyone, and never recover.”

Why It’s Harmful:

This thinking floods your system with anxiety, making it harder to concentrate, sleep, or retain information. It also fuels avoidance and procrastination.

How to Challenge It:

Ask: What’s the most likely outcome? What’s the worst-case scenario—and how would I handle it?

Reframe: “Failure would be tough, but I’ve overcome challenges before. I’ll learn and try again.”

3. Emotional Reasoning

Definition: Believing something is true because it feels true.

Doctor-Specific Example:

“I feel like a fraud, so I must be one.”

Why It’s Harmful:

Feelings are important—but they’re not facts. Emotional reasoning can override evidence of competence, leading to imposter syndrome and self-sabotage.

How to Challenge It:

Ask: What’s the evidence for and against this thought?

Reframe: “I feel uncertain, but I’ve prepared thoroughly and received positive feedback.”

4. Mind Reading

Definition: Assuming you know what others are thinking—usually something negative.

Doctor-Specific Example:

“My consultant thinks I’m incompetent because I hesitated during handover.”

Why It’s Harmful:

Mind reading creates unnecessary tension and self-doubt. It can damage relationships and erode confidence, even when there’s no real evidence.

How to Challenge It:

Ask: Do I have proof of what they’re thinking? Could there be another explanation?

Reframe: “I don’t know what they’re thinking. I’ll focus on what I can control—my preparation and performance.”

5. Overgeneralization

Definition: Drawing sweeping conclusions from a single event.

Doctor-Specific Example:

“I blanked on one question—this proves I’m not ready.”

Why It’s Harmful:

This error magnifies mistakes and minimizes successes. It can lead to hopelessness and disengagement from study or clinical work.

How to Challenge It:

Ask: Is this one moment representative of my overall ability?

Reframe: “I struggled with one question, but I’ve answered many others well. I’m improving.”

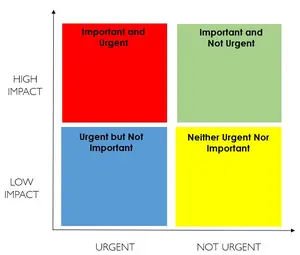

4 Steps to Challenge the 5 Most Common Thinking Errors

High-stakes exams are a pressure cooker for junior doctors. Long hours, limited sleep, and the weight of expectations can distort your thinking—often without you realizing it. These distortions, or cognitive errors, are automatic, emotionally charged, and deeply ingrained. They feel true, but they’re not.

Recognizing and challenging these errors is a key part of building resilience and studying smarter—not harder.

Step 1: Catch the Thought |

Step 2: Name the Error |

|

|

|

Goal: Build awareness of your internal dialogue. Thinking errors often operate just below the surface. They show up as automatic thoughts during moments of stress, fatigue, or uncertainty. The first step is to pause and notice them. Ask yourself:

Example: You blank on a practice question and immediately think, “I’m hopeless at this.” This is your cue. You’ve caught the thought. Now you can work with it. |

Goal: Label the distortion to reduce its power. Naming the thinking error helps you externalize it. It’s not who you are—it’s a cognitive habit. This step is about identifying which of the 5 most common thinking errors you’re dealing with. Ask yourself:

Example: “I blanked on one question—this proves I’m not ready.” |

Step 3: Challenge the Thought |

Step 4: Reframe It |

|

|

|

Goal: Test the thought like a hypothesis. This is where you shift from emotion to evidence. Treat the thought like a theory and ask whether it holds up under scrutiny. Ask yourself:

Example: “I’m hopeless at this.” → Evidence against: You’ve answered similar questions correctly. You’ve improved over time. You’re actively preparing. |

Goal: Replace the distortion with a balanced, empowering thought. Reframing doesn’t mean ignoring difficulty—it means interpreting it through a lens of growth, learning, and self-compassion. Instead of: “I failed. I’m not good enough.” Try “I didn’t pass this time. Many doctors don’t. I’m learning and improving every day.” Instead of: “I’m not ready.” Try “I’m not ready… yet.” |

The Power of "Yet"

One of the simplest and most transformative reframes is adding the word “yet.”

- “I haven’t passed… yet.”

- “I don’t understand this topic… yet.”

- “I’m not confident… yet.”

This tiny word shifts your mindset from fixed to growth. It reminds you that progress is possible, and that setbacks are part of the journey—not the end of it.

As we say in our book:

“The power of yet is that it builds a bridge between having a fixed mindset and having a growth mindset.”

Final Thought: You Are Not Your Thoughts

As a junior doctor, your mind is your most powerful tool—but it can also be your greatest source of stress. The pressure to perform, the fear of failure, and the constant comparison to peers can create a storm of self-doubt and distorted thinking. But here’s the truth:

You are not your thoughts.

You are the observer, the challenger, the re-framer.

Thinking errors—like catastrophizing, mind reading, and emotional reasoning—are not reflections of your character or competence. They are mental habits, shaped by stress, perfectionism, and years of high expectations. And like any habit, they can be changed.

By learning to catch, name, challenge, and reframe these thoughts, you begin to reclaim your mental clarity, emotional stability, and professional confidence. You stop reacting and start responding. You stop spiraling and start strategizing.

This is not just about passing an exam. It’s about building the psychological resilience to thrive in medicine—where uncertainty, complexity, and emotional intensity are part of the job.

As we say in our book:

“Deliberate, repeated practice of every single technique you choose to do will pay dividends. You’ll soon see – life will be so much better.”

So when the pressure builds, when the doubts creep in, when the voice in your head says, “I can’t do this”—pause. Breathe. And remember:

- You’re not ready… yet.

- You haven’t passed… yet.

- You’re not confident… yet.

But you’re learning. You’re growing. And you’re not alone.