- Home

- What is Deliberate Practice

What Is Deliberate Practice? A Smarter Way to Study Medicine

What is deliberate practice? It’s a structured, purposeful form of learning designed to target your weaknesses, push you beyond your comfort zone, and use feedback to drive continuous improvement. Unlike passive repetition, deliberate practice focuses on doing the right things, in the right way, with the right level of challenge to achieve meaningful progress.

This concept, first popularised by psychologist K. Anders Ericsson, helps explain how elite performers—from concert pianists to Olympic athletes—reach mastery. In the context of medical exams, deliberate practice means identifying the areas where you struggle most and working on them systematically, rather than defaulting to what feels familiar or easy.

As our book puts it :

“Deliberate practice means working on things you don’t like or can’t do well, getting feedback, and repeating the process until you improve.”

For doctors preparing for exams, this means embracing discomfort, seeking targeted feedback, and refining your skills through focused repetition—not just reviewing what you already know.

What is Deliberate Practice and Why It Works

Deliberate practice works because it’s designed to stretch your current abilities. It forces you to engage deeply with the material, confront your limitations, and refine your skills through repetition and reflection. Unlike passive study methods, it demands full attention and effort.

This kind of practice also builds resilience. When you regularly tackle difficult material, you become more comfortable with discomfort—and more confident in your ability to improve. Over time, this leads to better performance, greater retention, and a stronger sense of control over your learning.

Deliberate Practice vs. Passive Study

Most students spend the majority of their time in the comfort zone—reviewing notes, re-reading textbooks, or doing practice questions they already know how to answer. This feels productive and safe, but it rarely leads to meaningful improvement. It’s familiar territory, but it doesn’t stretch your abilities.

Deliberate practice, by contrast, lives in the learning zone. This is where you tackle material that’s just beyond your current level of mastery. It’s where you make mistakes, receive feedback, and refine your approach. It’s mentally demanding, sometimes frustrating—but it’s also where real progress happens.

Then there’s the panic zone—where the challenge is too far beyond your current ability. In this zone, tasks feel overwhelming, anxiety spikes, and learning shuts down. You’re not building skills here; you’re just trying to survive. Spending too much time in the panic zone can lead to burnout and discouragement.

The key is to operate in the learning zone—just outside your comfort zone, but not so far that you tip into panic.

Our book illustrates this with a simple but powerful analogy:

“When Patsy was young and learning piano, she wanted to be a reasonably accomplished musician. But to improve, you don’t simply play tunes you like. You practise the difficult sections.”

For medical students and doctors, this might mean focusing on clinical scenarios you find confusing, explaining complex topics aloud, or simulating exam conditions with time pressure and feedback. It’s not easy—but it’s where growth happens.

How to Use Deliberate Practice

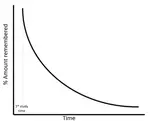

Why Deliberate Practice Wins: The Story Behind the Curve

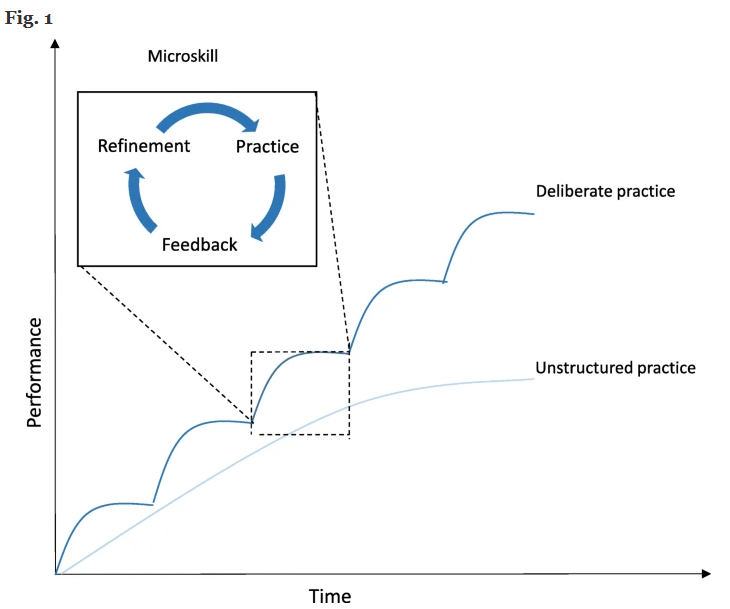

Figure 1 published in BMC Medication Education Journal tells a powerful story: not all practice is created equal. While unstructured practice creeps forward slowly, deliberate practice climbs in bold, upward steps—each one representing a breakthrough in skill, confidence, and performance.

This isn’t just a graph—it’s a roadmap to mastery. Every step in the deliberate practice curve is earned through focused effort, feedback, and refinement of microskills. It shows that real progress doesn’t come from doing more—it comes from doing better.

Meanwhile, the smooth, shallow slope of unstructured practice is a warning: without intention and feedback, your growth will stall. But with deliberate practice, you’re not just learning—you’re leveling up.

Five Ways to Apply This Insight For Your Exam Preparation

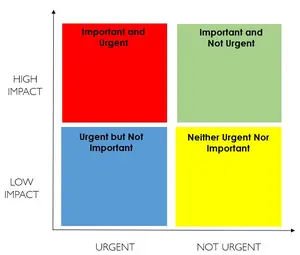

1. Identify Your Weaknesses

Start by reviewing past performance. Which topics do you avoid? Which question types trip you up? Where do you feel least confident?

Use mock exams, feedback from supervisors, or self-assessment tools to pinpoint your gaps.

2. Set Specific Goals

Don’t just aim to “get better at cardiology.”

Set a clear, measurable goal like:

- “Improve my ability to interpret ECGs in under 2 minutes” or

- “Answer 10 MCQs on heart failure with 80% accuracy.”

Specific goals help you stay focused and track your progress.

3. Practise With Intention

Choose tasks that are just beyond your current ability. This might mean:

- Attempting difficult MCQs under timed conditions

- Writing short-answer responses without notes

- Practising oral responses to clinical scenarios

The key is to challenge yourself—not overwhelm yourself.

4. Get Feedback

Feedback is essential. Without it, you won’t know what to improve. This can come from:

- A supervisor or study group

- Self-review (e.g. using the double-take method)

- Comparing your answers to model responses

Be open to critique. It’s not a judgment—it’s a tool for growth.

Distributed practice and active recall methods can be useful here.

5. Develop the Mental Model of Repeat and Refine

Deliberate practice is iterative. You try, fail, adjust, and try again. Over time, your performance improves—not because you’re doing more, but because you’re doing it better.

Real-World Example: Ali’s Interview Breakthrough

Ali, an international medical graduate, was trying to get onto an accredited training program. Her consultants told her she needed to be more confident, and her voice was too soft. During coaching, she recorded her answers to common interview questions, reviewed them, and received structured feedback.

She used a technique called the “filleted fish” structure to organise her responses: head (introduction), spine (main flow), ribs (subtopics), and tail (conclusion). With repeated practice, her voice became stronger, her answers clearer, and her confidence grew. She was accepted into her dream program.

What the Research Says

Ericsson’s research on expert performance found that deliberate practice is the single most important factor in achieving mastery. It’s not talent or time—it’s how you practise that matters.

In medicine, this principle has been applied to everything from surgical training to diagnostic reasoning. A 2015 study in Medical Education found that trainees who engaged in structured, feedback-driven practice improved significantly faster than those who relied on unstructured repetition.

Deliberate practice is also mentally taxing. It requires focus, effort, and recovery. That’s why short, intense sessions (e.g. 50 minutes with a 10-minute break) are more effective than long, unfocused marathons.

Some Mistakes to Avoid

- Practising what you already know: It feels good, but it doesn’t help you grow.

- Avoiding feedback: Without feedback, you’re just reinforcing bad habits.

- Overloading yourself: Deliberate practice is intense. Quality matters more than quantity.

- Skipping reflection: Take time to review what worked, what didn’t, and what to change next time.

What Can You Do Right Now

|

Tools that Can Help

|

Deliberate practice is not glamorous. It’s not easy. But it works.

It’s the difference between going through the motions and making real progress. It helps you build confidence, competence, and control over your learning. And in a system that demands high performance under pressure, that’s a powerful advantage.

If you want to study less and succeed more, deliberate practice isn’t optional—it’s essential.

References

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406.

Ericsson, K. A. (2004). Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Academic Medicine, 79(10 Suppl), S70–S81.

Ericsson, K. A. (2008). Deliberate practice and acquisition of expert performance: A general overview. Academic Emergency Medicine, 15(11), 988–994.