- Home

- What Is a Mindset

- Fear of Failure

Facing the Fear of Failure: Why Growth Mindset Matters in Medicine

Failure. It’s a word that carries weight - especially in medicine, where the stakes are high and the margin for error feels razor-thin. For junior doctors, the fear of failure can be overwhelming. It can manifest as anxiety before ward rounds, hesitation in decision-making, or burnout from the constant pressure to perform.

And it’s not just clinical pressure. Many junior doctors are also preparing for postgraduate exams

- studying late into the night,

- juggling revision with long shifts, and

- feeling the weight of expectations from themselves and others.

The fear of not passing, of not progressing, can feel just as intense as the fear of making a mistake on the ward.

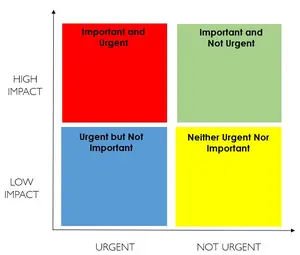

But here’s the truth: failure is not the enemy. A fixed mindset - believing that your abilities are static and that mistakes define you - is.

Why Fear of Failure Is So Common (6 main reasons)

Junior doctors often enter the workforce after years of academic achievement. The transition from structured exams to the unpredictable reality of clinical practice can be jarring.

Add to that the pressure of ongoing assessments and specialty training exams, and it’s no wonder many feel like they’re constantly being tested.

For junior doctors, this fear is often amplified by a combination of personal, professional, and systemic factors. Here are some common ones that we see:

1. High-Stakes Environment

|

2. Constant Evaluation

|

3. Imposter Syndrome |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Perfectionist Tendencies

|

5. Cultural Expectations

|

6. Personal Investment

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Growth Mindset: A Better Way Forward

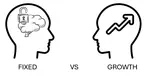

The concept of a growth mindset, introduced by psychologist Carol Dweck, is the belief that intelligence, skills, and abilities are not fixed traits—they can be developed through effort, learning, and persistence (Dweck, 2006). In contrast to a fixed mindset, which sees failure as a reflection of inherent inadequacy, a growth mindset views failure as a stepping stone to improvement.

For junior doctors, this mindset is not just helpful—it’s essential. Medicine is a career of lifelong learning, and the ability to adapt, reflect, and grow is what transforms a good doctor into a great one.

Here’s what adopting a growth mindset can look like in practice:

Viewing feedback as a tool, not a threat:

Feedback becomes a guide for improvement rather than a judgment (Teunissen & Bok, 2013). Here are some characteristic responses for a doctor with a growth mindset:

- Feedback is not a judgment—it’s information.

- Constructive criticism helps you refine your clinical reasoning and communication.

- Embracing feedback builds resilience and accelerates learning.

Understanding That Setbacks Are Part of Progress:

Mistakes are reframed as learning opportunities, not personal flaws (Artino et al., 2012). So a doctor with a growth mindset considers:

- Mistakes and missed answers are part of the journey.

- Every setback is a chance to identify gaps and strengthen your foundation.

- Growth comes from reflection, not perfection.

Recognizing that confidence grows through experience, not avoidance:

Facing challenges builds competence and self-efficacy (Ten Cate et al., 2011). So a doctor with a growth mindset considers:

- Confidence isn’t innate—it’s built through repeated exposure and effort.

- Avoiding challenges delays growth; facing them builds competence.

- Each difficult shift or exam is a chance to stretch your limits.

Supporting Peers Without Judgment, Knowing Everyone Is Learning:

A growth mindset fosters collaboration and psychological safety in teams (Edmondson, 1999). So a doctor with a growth mindset considers:

- Everyone is navigating their own learning curve.

- A growth mindset fosters collaboration, not competition.

- Empathy and shared learning strengthen team dynamics.

Protecting wellbeing by accepting imperfection:

Self-compassion and acceptance reduce burnout and promote resilience (Neff, 2003). So a doctor with a growth mindset considers:

- You don’t have to be flawless to be effective.

- Accepting imperfection reduces anxiety and prevents burnout.

- Self-compassion is a key part of professional sustainability.

Approaching Exams as Opportunities to Grow, Not Just Hurdles to Clear:

Exams become part of the learning journey, not just a hurdle to clear (Cook & Artino, 2016). So a doctor with a growth mindset considers:

- Exams test knowledge, but they also reveal areas for development.

- A growth mindset turns revision into meaningful learning.

- Success is not just passing—it’s evolving as a clinician.

Here are some ideas on how to change your mindset.

Reframing Failure

Failure isn’t a verdict—it’s data. It’s feedback from reality, showing you what didn’t work so you can explore what might. In medicine, where the learning curve is steep and the stakes are high, failure can feel personal. But it’s not a reflection of your worth—it’s a reflection of your process.

Reframing failure means shifting from shame to curiosity:

- Instead of asking, “What’s wrong with me?”, ask “What can I learn from this?”

- Instead of hiding mistakes, explore them with openness and humility.

- Instead of fearing failure, use it as fuel for growth.

In clinical practice, exams, and teamwork, the ability to reflect, adapt, and grow is far more valuable than getting everything right the first time. Medicine isn’t about perfection—it’s about progress.

Final Thought

You are not your exam result.

Not your last shift.

Not your last mistake.

You are a work in progress - and that’s not a flaw, it’s a strength.

Every challenge you face, every moment of doubt, every setback is part of a larger story: one of growth, resilience, and becoming. The fear of failure may visit often, but it doesn’t have to stay. You can choose to meet it with compassion, curiosity, and courage.

So the next time fear creeps in, remember:

- Your brain is a muscle—strengthened by effort, not weakened by struggle.

- Your mindset is a choice—one that shapes how you learn, lead, and live.

- Your future is still being written—and you hold the pen.

Choose growth.

References

- Cook, D. A., & Artino, A. R. (2016). Motivation to learn: An overview of contemporary theories. Medical Education, 50(10), 997–1014. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13074

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

- Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

- Teunissen, P. W., & Bok, H. G. J. (2013). Believing is seeing: How people's beliefs influence goals, emotions and behavior in medical education. Medical Education, 47(11), 1064–1072. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12228

- Ten Cate, O., Kusurkar, R. A., & Williams, G. C. (2011). How self-determination theory can assist our understanding of the teaching and learning processes in medical education. Medical Teacher, 33(12), 961–973. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.595435

- Artino, A. R., Dong, T., DeZee, K. J., Gilliland, W. R., Waechter, D. M., Cruess, D. F., & Durning, S. J. (2012). Development and initial validation of a survey to assess students’ self-efficacy in medical school. Military Medicine, 177(SUPPL.1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-12-00240