- Home

- Study Smarter

- What is Cramming

What Is Cramming—and Why It Fails Doctors in High-Stakes Exams

If you’ve ever pulled an all-nighter before an exam, you already know what cramming feels like. But what is cramming, really? It’s the practice of studying intensively over a short period—usually right before an exam - often involving long hours, minimal breaks, and a frantic attempt to absorb as much information as possible.

While cramming may feel productive in the moment, it’s one of the least effective ways to retain information - especially for complex, high-volume exams like those in medicine.

Why Cramming Doesn't Work

Understanding what is cramming helps us see why it fails. Cramming relies heavily on short-term memory. It might help you recall facts for a few hours, but it does little to support long-term retention or deep understanding. Here’s why:

Cognitive overloadYour brain can only process so much at once. Cramming floods your working memory, leaving little room for consolidation. |

Poor SleepCramming often cuts into rest, which is essential for memory consolidation and emotional regulation. |

Stress and AnxietyThe pressure of last-minute study increases cortisol, which impairs memory and focus. |

No Time for FeedbackCramming doesn’t allow for testing, reflection, or correction - key components of effective learning. |

“Cramming gives you the illusion of productivity and the reality of panic.”

Some Common Myths About Cramming

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| “I work better under pressure.” | You may feel more focused, but your retention and performance suffer. |

| “I don’t have time to study earlier.” | You don’t need more time—you need better strategy. Even 30 minutes a day adds up. |

| “Everyone crams.” | Many do—but many also fail. High performers use smarter methods. |

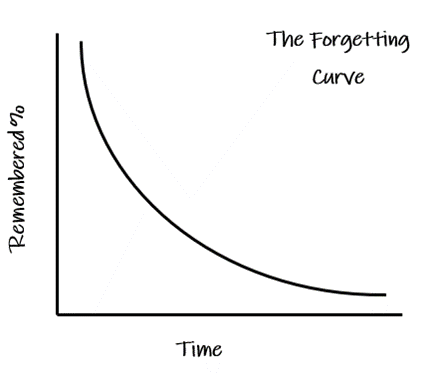

The Science Behind Forgetting

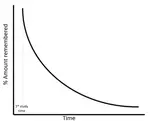

To truly understand what is cramming, we need to look at how memory works. The Ebbinghaus forgetting curve shows that we forget up to 75% of new information within 24 hours if we don’t review it.

Cramming ignores this curve. It may help you feel familiar with the material, but that familiarity fades quickly—especially under exam pressure.

In contrast, spaced repetition and active recall flatten the forgetting curve and build durable, retrievable knowledge.

Real-World Example: Millie’s Story

Millie, a dermatology registrar, had been using spaced repetition and active recall successfully. But as her final exam approached, anxiety took over. She reverted to cramming—studying every spare moment, sacrificing sleep, and barely seeing her children. She became overwhelmed and broke down in tears.

Her coach helped her understand what cramming is and why it wasn’t working. She reduced her study hours, planned her days, and prioritized rest. A week later, she felt calmer, more focused—and passed all her exams with merit.

What to Do Instead

If you’re wondering how to avoid cramming, here are five proven strategies:

1. Start Early, Even If It’s Small

You don’t need to study for hours a day from the beginning. Start with short, focused sessions. The earlier you begin, the more you can space your learning—and the less you’ll need to cram. Here are some ideas on types of recovery breaks you may need.

2. Use Spaced Repetition

Review material at increasing intervals. This strengthens memory and reduces the need for last-minute review.

3. Test Yourself Regularly

Active recall (e.g. flashcards, practice questions, oral summaries) is far more effective than rereading. It also helps you identify gaps early—when you still have time to fix them.

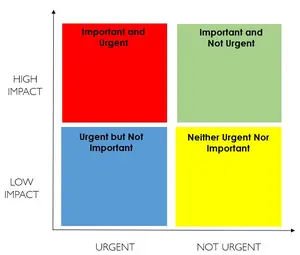

4. Schedule Your Study

Plan your week in advance. Allocate time for study, rest, and life. A predictable rhythm reduces stress and improves consistency. Here are some ideas on creating a study schedule that works.

5. Prioritize Sleep and Recovery

Sleep is not a luxury—it’s a study tool. Memory consolidation, emotional regulation, and cognitive performance all depend on it. Here are some ideas on sleep hygiene.

What You Can Do Right Now

- Identify one topic you’ve been putting off. Schedule it for tomorrow morning.

- Write five questions on today’s study material. Test yourself in 48 hours.

- Cancel one cramming session this week and replace it with a walk or early night.

- Download a spaced repetition app (like Anki) and start building your deck.

Final Thoughts

Understanding what cramming is is the first step toward breaking free from a cycle that many doctors fall into—especially under pressure. Cramming may feel like a necessary response to limited time and rising anxiety, but it’s a short-term fix that undermines long-term success. It sacrifices retention, wellbeing, and confidence for a fleeting sense of productivity.

The truth is, effective study isn’t about intensity—it’s about consistency. It’s about building habits that support your memory, your mindset, and your life outside of medicine. A smarter approach—one that includes spaced repetition, active recall, and structured scheduling—can help you learn more deeply, perform better under pressure, and stay well while doing it.

You don’t need to be perfect. You just need to start. Replace one cramming session with a planned review. Choose one topic to revisit with active recall. Protect one evening for rest. These small shifts add up—and they move you toward a more sustainable, confident, and successful exam journey.